___________

___________

Johann Sebastian Bach / English Suite No. 6 in D Minor, BWV 811 (1715-20)

Prélude

Allemande

Courante

Sarabande - Double

Gavotte I & II

Gigue

___________

Maurice Ravel / Sonatine (1905)

Moderé

Mouvement de Menuet

Animé

__________

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart / Phantasia in C Minor, K. 475 (1785)

__________

Sergei Prokofiev / Sonata No. 5 in C Major, Op. 38/135 (1923, revised 1953)

Allegro tranquillo

Andantino

Un poco allegretto

________________

Return to Form

(Notes © 2024 by Brian Taylor)

The sonata da camera — a prelude followed by a series of dances suitable for court but not church (which would call for a dance-less sonata da chiesa) — reached its zenith with Bach’s English Suite No. 6 in D Minor. A towering Prelude, which begins with a slow introduction that bursts into a large ternary form replete with multiple theme groups, a veritable development section, and a recapitulation, lays the groundwork for what composers like Beethoven would later create with what became known as sonata-allegro form.

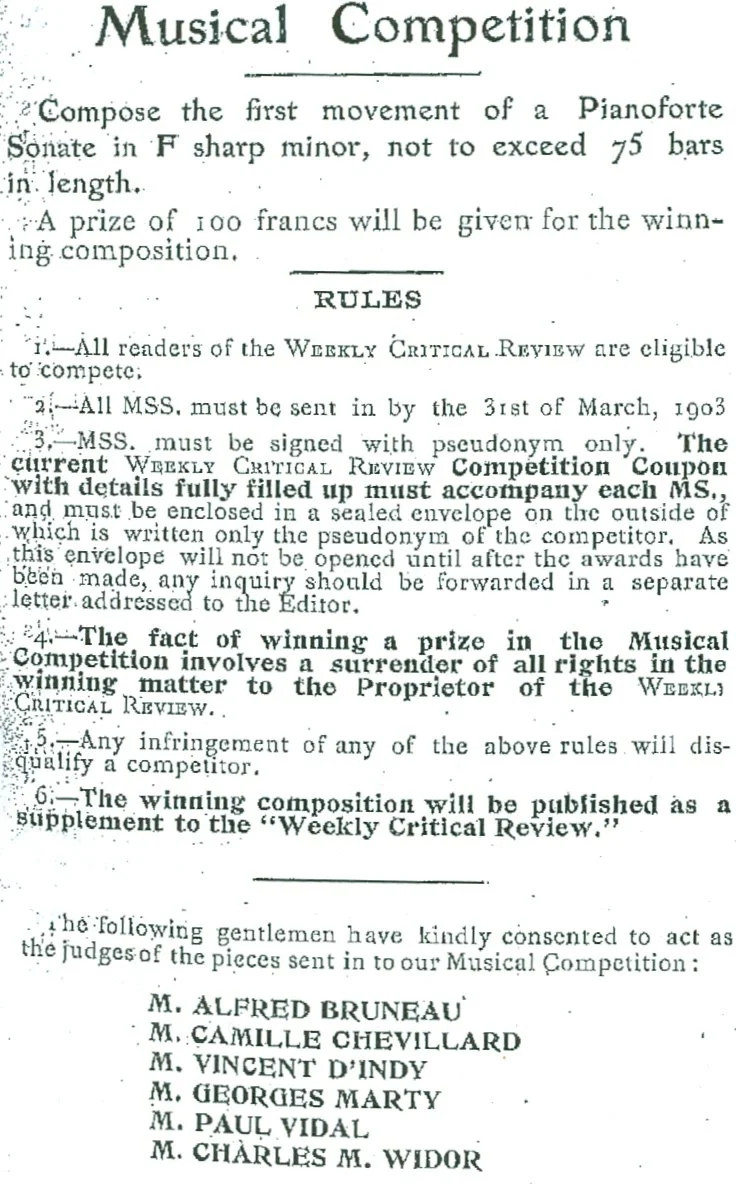

Some two centuries later, Ravel’s Sonatine pays homage to the tidy, Apollonian classical sonata with a perfume of nostalgia. Famously, Ravel’s impetus to compose the piece was a competition in the Paris Weekly Critical Review. Technically, the entry placed under the pseudonym Verla didn’t win the competition (the paper went bankrupt; there was no winner), but his completed three-movement piece, a pristinely distilled apogee of sonata form, walked away with the winnings — it was so successful, its publisher Durand offered Ravel an exclusive publishing contract.

Ravel’s autograph manuscript, in which par Verla (anagram, and pseudonym) is crossed out.

When Ravel Composed to Order, by Michel Dimitri Calvocoressi, appearing in 1941 in Music & Letters.

Weekly Critical Review, 12 March 1903 and was then repeated on 19 March, 9 and 23 April.

_____________

The key of C minor is associated with pathos and drama. Mozart’s Phantasia in C Minor, K. 475, was published, as Opus 11, as preludial companion to the composer’s only C minor piano sonata, K. 457, which he completed seven months earlier. Opus 11 was dedicated to — “composed for,” rather — Therese von Trattner.

The wife of Johann Thomas von Trattner, preeminent Viennese publisher forty years her senior, Therese was not only a wealthy pupil of the composer, but arranged for him to live in their Vienna home and hosted concerts of his music in their salon. What motivated Mozart to compose such powerful, emotional music for Therese, who would also go on to become godmother to his children? (Speculation has been fueled by Trattner’s refusal to return Mozart’s letters to his wife, Constanze, upon his death.)

Mozart’s autograph manuscript.

Mozart was at the peak of his career in 1785, and had recently settled in Vienna — a hot commodity in the big city — and married. He also began to make acquaintance with the music of Bach and Handel, which influenced and expanded his musical imagination. His skills as an improviser, creating “Phantasias” on the spot, were especially renowned, and this piece survives as the next best thing we’ll get to a recording of Mozart rhapsodizing at the keyboard. Seemingly taking a thematic cue from Bach’s Musical Offering (also in C minor), Mozart whipped up an impromptu opera-in-miniature. No mere introduction to a sonata — it’s several scenes in a hero’s journey.

An expanded riff in octaves on Bach’s “royal theme” immediately launches a mysterious peregrination to distant lands, first resting with patience and readiness at B minor. However, B minor proves an illusion — a simple, yearning air in D major is disrupted by a squall (Allegro), and our hero is swept up and down the keyboard, diving, then taking taking flight before alighting into a scene out of an opera buffa (Andantino, in B-flat major). The plot thickens again (Piú Allegro): a struggle of fates, until we eventually return, wounded yet breathing, to C minor.

A reprise of the murky motive in octaves communicates a lesson learned, and at the same time, a shade of existential dread (in a fateful cadence that augurs Nicholas Britell’s ‘Main Theme’ for HBO’s Succession).

_____________

Prokofiev’s rarely played Fifth Sonata has a reputation as the ugly step-sibling among his nine piano sonatas. Unfairly neglected, the Piano Sonata No. 5 in C Major is an exemplar of style. Prokofiev’s Jekyll & Hyde duality — brutal “bad boy” of the conservatory and lyrical tunesmith — steeped in 1920’s Paris and delivered in a neo-classical, Schubert-esque frame.

Prokofiev revised the sonata thirty years later in 1953. An anthropological master class in the art of composition, it was his final realized project. Whether motivated by anti-'Formalist’ authorities, or merely a desire to revisit and improve the original score, his changes to the first two movements are largely superficial.

In the first movement — a fairytale in sonata-allegro form — he edits and clarifies the second theme, decluttering and removing extraneous density; and he thins out the coda’s convoluted stacking of ideas, replacing a stunning shocker with a wry, winking comment. Easier to play and easier for the listener to take in.

He makes surface adjustments — oddly tinkering with the melody’s notes here and there — in the ironic second movement, a macabre dance in three, more minuet than scherzo, that brings to mind birds and marionettes.

Prokofiev gives the third movement more of a makeover, adhering to his original ideas, but rewording and reimagining them — tightening here and fleshing-out there. The climatic return of the main theme is given a more justified motivation, and, perhaps, a shade of sentimentality. The movement becomes a dialogue between the present and the past — a musical reminiscence.

____________